- Home

- John Dougherty

Bansi O'Hara and the Bloodline Prophecy Page 2

Bansi O'Hara and the Bloodline Prophecy Read online

Page 2

Mrs Mullarkey bristled. ‘Funerals, is it, Mrs High-and-Mighty O’Hara?’

‘High-and-Mighty? What do you mean by that, Nora Mullarkey?’

‘What, are you going to tell me now that your family isn’t descended from the High Kings of Donegal like you’re always crowing about, then?’

‘Well, and so what if we are? Can I help it if my family has an illustrious heritage? And one that I don’t want to see ending in little pieces all over the road in the middle of a herd of cows!’

‘I stopped, didn’t I? Which is more than I can say for you, going on about your blessed High Kings of Donegal all the time . . .’

Sean sighed, shook his head and turned back to the cows. ‘Ho, there! Come on, now!’ he called, and the cattle slowly began to lumber off through the gate into the field. Behind him, over the sound of the continuing argument, came the grind and crunch of Mrs Mullarkey finding first gear. He looked round to see the car leap wildly forward, roaring like some fearsome beast, and disappear from view.

Bansi O’Hara could hardly contain her excitement. Granny O’Hara had visited her and her parents in London quite often – and sometimes even came to look after Bansi when her parents’ work took them away from home during term-time – but at ten years old this was her first trip to Granny’s house in Ballyfey, the house her father had grown up in. She stood at the front of the ship, feeling the cold salt sea spray her face, and strained her eyes to catch her first glimpse of Ireland.

Her father, a tall, curly-haired man with rugged Irish good looks and a permanent twinkle in his eye, leaned on the railing next to her. ‘Are we nearly there yet?’ he asked teasingly.

Bansi tipped her head accusingly. ‘Dad! Be fair! When was the last time I ever said that?’

‘Oh . . . about five minutes ago!’

‘I did not!’ Bansi retorted, scandalized. ‘I said no such thing!’

‘Ah . . . no, you’re right, that was me that time, too, wasn’t it?’

‘Yes,’ said Bansi. ‘And the time before that, and the time before that as well!’

‘No, be fair yourself, the time before that was your mother . . . talking of whom, where’s she gone?’

‘Right here!’ Bansi’s mum came up behind them, blinking as the sea-breeze whipped black trails of hair across her pretty round face. Even windswept, and even in her faded denims, she somehow managed to look – as Bansi thought of it – mischievously elegant, as if her beauty refused to take itself seriously. In each slender hand she carried a polystyrene cup of tea. ‘I got this for you,’ she said, offering one to her husband.

‘Asha, my love, you’re an angel.’ Bansi’s dad took the cup and warmed his hands on it, the lines round his eyes creasing in a smile that made him look wise as well as kindly. He glanced up as something in the sky caught his attention. ‘Now would you look at that!’

A beautiful white swan was winging its way towards the ferry. The passengers on the deck looked up, shielding their eyes against the day’s brightness. Bansi felt her heart leap as she gazed at the creature; the daylight danced in dazzling reflection across the water, a path to lead the swan straight to the ship – and to her. For a moment she had the feeling of a connection, a line as intangible and yet as real as the sunlight shining on the sea, stretching between herself and the great bird.

‘That’s something you don’t see every day,’ Bansi’s mum remarked. ‘Isn’t it lovely?’ She smiled down at her daughter; and Bansi smiled back.

The swan turned and kept pace with the ship, just low enough for the little brown man-goblin on its back to get a good view of the passengers without being spotted.

‘That’s her, Tam!’ he said. ‘The Child of the Blood of the Morning Stars!’

‘Which one?’ the swan asked.

Pogo rolled his eyes. ‘Don’t you know anything about mortals?’

The swan shrugged, and Pogo was thrown suddenly forwards. He cursed, flinging his arms round his companion’s neck.

‘Watch out!’ he snarled. ‘Right; now look and listen, so you’ll know who it is we’re here to protect. Do you see the couple right at the bow end of the deck, looking straight at us – she, brown of skin with black hair that falls around her shoulders; he, light, with sandy curls?’

The swan nodded, and again Pogo was jerked forward. As he clutched at its neck, he was sure he heard it snigger.

‘You do that again and I’ll boot your next egg back where it came from,’ Pogo growled. ‘Now: those two are the parents, each descended from one of the two Morning Stars – he from Caer and she from Avalloc. Look at the child beside them: the slender wee girl with golden-brown skin, fairer than her mother’s but darker than her father’s. Do you see who I mean? She has her mother’s black hair, and a face that’s strong like her da’s but much more elfin. Can’t tell from up here which side she gets her eyes from, mind . . .’

‘Both,’ Tam said immediately. ‘They’re even larger than the mother’s, but the same sort of round almond shape. The grey-green colour’s from the da, but they’re brighter than his, with a dark rim to the iris. Very striking.’

Pogo started. ‘You never saw that from up here?’

‘I did. I’m a púca, don’t forget. So you reckon that’s her? She’s very slight, isn’t she? I wouldn’t give her much odds in a fight. How can you be sure she’s the one?’

‘I may not have any of what you’d call magic,’ the little man retorted coldly, ‘nor eyesight as sharp as yours either; but I have the instincts of my people. And I know the story of the Morning Stars, too, which is more than it seems you do. Do you not know the story of how Avalloc fled to the ancient forests of India, and Caer to the hills of Donegal? I’m sure, all right. She’s the one. I wish I could be half so certain he won’t get to her before we do.’

Swans can’t smile at all, let alone grin broadly, but Tam made the best effort he could. ‘How is that ever going to happen? Have a bit of sense, Pogo! Come on, admit it – we’re way ahead of him.’

Pogo snorted. ‘Way ahead of him, indeed,’ he muttered. ‘Have you forgotten, Tam? It was the Dark Lord’s magic that discovered the child was coming within reach of the gate on Midsummer’s Eve, not Caithne’s. It’s only by sheer luck she found out about it at all. If you ask me, we’ve been trying to catch up with him and his forces all the way.’

Tam chuckled softly. ‘Well, we’ve not only caught them up, we’ve overtaken them. So stop worrying.’

Beneath the surface of the water, a shape tracked the ship. Fluidly, relentlessly, it moved through the water like some aquatic predator, its focus entirely on the hull that cut through the sea above it.

Had you been there to see it, you might not have recognized it at first, so easily did it move, so naturally did it seem to belong in the undersea environment. You might well have taken it for some strange marine creature. Only as you drew close would you have realized that it was a boy – a dark-haired boy with a cruel, cunning face and no apparent need to breathe. His wolfskin cloak flowed around him like the sea itself, as he cut through the water more swiftly and steadily than a hunting shark.

Chapter Three

Bansi and her parents leaned over the railing, watching the swan. Ahead of them the harbour was now in clear sight, and beyond it Bansi could see hills in the distance, looking somehow wilder and greener than the ones at home. She felt a sudden surge of excitement, so much so that she could hardly keep still, and for want of any other release she hugged her mother tight, making her laugh.

‘Tell you what, we’re a wee bit ahead,’ her dad remarked, glancing at his watch. ‘With any luck we might catch the earlier train and be with your granny before tea.’

Bansi’s mum put her hand to her mouth. ‘Oops!’ she said. ‘I forgot to tell you! Your mother phoned last night while you were in the shower, to say we needn’t take the train. Her friend’s bringing her to pick us up . . . What’s wrong, love?’

Bansi’s dad had gone pale. ‘Which friend?’

‘Mrs . . . Mullarkey, I think she said. Could that be right?’

Bansi’s dad sank his head into his hands and groaned.

‘What is it, Dad?’ Bansi asked, grinning. Her dad’s overacting always amused her. ‘She can’t be that bad!’

‘Ach, no, it’s not that, sweetheart. She’s very nice, Mrs Mullarkey, in her own way. It’s just . . . well, she drives like a maniac. Put her behind the wheel of a car and she goes completely barmy. They’ve had to armour-plate all the hedgehogs in the county because of her. And the other thing is – well, your granny and Mrs Mullarkey have been friends since they were little girls, and they’ve somehow never lost that competitive streak that some children have with one another . . .’

The green Morris Minor Traveller screeched into the ferry terminal car park and – its driver utterly ignoring her passenger’s frenzied shrieking of, ‘Nora, you’re going too fast you’re going to hit those people WATCH OUT!!!’ – came to a surprisingly sudden halt in one and a half parking spaces. After a moment, a couple of nervous-looking pedestrians climbed back down from the roof of the car next to it and hurried away.

‘There, now! Didn’t I tell you?’ Mrs Mullarkey beamed at the world in general. ‘Nothing to worry about, and we’re here in plenty of time for a cup of tea, too.’ She reached into the back of the car for her walking stick and made a great show of leaning on it to help herself out. Not to be outdone, Mrs O’Hara did the same, grasping the top of her stick with both hands. She paused as she stood up, as if in pain but not wanting to complain.

Mrs Mullarkey glared at her for a moment. Then she bent over ever so slightly, as though giving in just a little to a backache she had been heroically struggling against. Mrs O’Hara glared back, winced, bent over just a little more than that and began to limp off towards the terminal.

Mrs Mullarkey groaned, crooked her back a little more and hobbled after her friend, just fast enough to overtake her.

Less than half a minute later, the doors to the ferry terminal burst open. Two little old ladies dashed in, hobbling rather more quickly than the average person is capable of sprinting and both groaning like a pig with an elephant on its head. Their chins practically touching their knees, they bowled over the terminal manager and an entire troop of scouts before screeching to a halt in a dead heat at the tea-shop counter.

Stiffly and with great ceremony, the two women gradually stood upright, pressing down on the tops of their walking sticks. The man behind the counter slowly raised himself from the floor, where he had thrown himself in panic.

‘Can I get you anything, ladies?’ he asked hesitantly.

Mrs O’Hara turned to her friend. ‘You first, Nora,’ she said.

‘Oh, no, Eileen,’ Mrs Mullarkey replied. ‘After you, I’m sure.’

Half an hour later, just as the ferry was docking, a soft ripple spread across the water in a secluded bay not far from the harbour. A gull resting on the surface took off in a sudden flurry of panicking wings. Water cascading from his form, the boy with the cruel face emerged from the shallows, inhaling deeply and hungrily but without desperation. Quickly, he drew the hood of the wolfskin over his head and gathered the folds of his cloak around him.

Moments later, the grey wolf turned and sniffed the air.

* * *

‘Granny!’ shouted Bansi, throwing herself into her grandmother’s embrace. ‘Granny!’

‘Careful, Bansi!’ laughed her mother, just as Mrs Mullarkey was saying, ‘Now, Eileen, you want to go easy, there. What about your lumbago?’

Bansi’s grandmother glared at her friend. ‘Lumbago, Nora? Whatever gave you that idea?’ She stood up, holding Bansi close to her. ‘I’ve never had trouble with lumbago. It’s your own lumbago you need to be careful of.’

Mrs Mullarkey straightened up visibly, to such an extent that behind her the terminal building appeared to be leaning over slightly. ‘What do you mean, Eileen? Have you forgotten the state you were in when we got here after that long drive? I thought you were never going to stand upright again, your back was giving you such trouble.’

Granny O’Hara bristled. ‘What I remember, Nora Maura Margaret Mullarkey, is wondering how you could see where you were going, you were so bent over. I felt quite sorry for you, so I did . . .’

‘Sorry?’ repeated Mrs Mullarkey, outraged. ‘ You feeling sorry for me? Oh, that’ll be the day, Eileen, that certainly will . . .’

Bansi looked at her father. ‘Told you,’ he mouthed.

A few minutes later, a party consisting of a ten-year-old girl, her parents, and the two most vertical elderly ladies ever seen in those parts, made their way across the car park to where Mrs Mullarkey’s old green Morris Minor Traveller was waiting for them.

‘My goodness, look!’ Granny O’Hara suddenly exclaimed as a magnificent white swan flew directly overhead.

‘It’s following you about, Bansi!’ Asha O’Hara teased her daughter. Mrs Mullarkey cast a sharp, enquiring look at them both – but especially at her friend’s granddaughter.

Bansi was staring after the bird, dazed by the sudden resurgent feeling of connection that washed over her like a wave. For a moment she felt submerged in a dream, as if the world around her was only half-real, and there was something else beyond it that she could have reached out and touched had she only known how.

‘Wakey, wakey, dreamer,’ her dad teased, nudging her out of the way as he loaded the luggage into the back of the car. ‘We’ve got a long old trek ahead of us.’

Eileen O’Hara nodded. ‘We have that, Fintan. We’ll do a bit of sightseeing on the way, just to break the journey up a bit. Make a day of it. Provided that Nora doesn’t break all of us up on the road first with her driving, that is,’ she added with a withering look at her friend.

A minute or so later, Bansi was gritting her teeth and holding on tight as the green Morris Minor Traveller roared out of the harbour car park. It cornered sharply, narrowly missing a couple of thankfully quite agile pedestrians, and turned towards Ballyfey.

None of the occupants noticed the swan, far above and matching their speed perfectly.

Nor did they notice the grey wolf that tracked them stealthily across country, keeping itself well hidden from view.

Chapter Four

Night was beginning to fall by the time they neared home. Fintan O’Hara was fast asleep in the back of the car, long legs folded uncomfortably behind the driver’s seat, head slumped awkwardly against the window. Asha O’Hara, mirroring him, slumbered against the opposite window, her Asian good looks only slightly marred by the trickle of dribble oozing from her open, snoring mouth. Between them, Bansi was sleeping soundly, her dreams filled with the startlingly beautiful scenery of the day’s drive.

‘It’s been a long old day for them, hasn’t it?’ Nora Mullarkey remarked.

‘It has that, Nora,’ her friend said. ‘They’ll have had to get up in the middle of the night to get to the ferry in—Look out!’

For the second time that day, the car screeched urgently to a halt. Its rear wheels skidded violently. The dark shape in the road turned; two yellow eyes stared at them malevolently, gleaming in the headlights. Then it was gone.

The two old women looked at each other.

‘What was that?’ Eileen O’Hara asked shakily.

Nora Mullarkey looked grim. ‘A wolf,’ she said. ‘Without a shadow of a doubt, that was a wolf in the road.’

Eileen O’Hara looked at her friend in amazement. She laughed nervously. ‘Nora, talk sense! You know as well as I do that there’ve been no wolves in Ireland for hundreds of years.’

‘Aye, well it was no ordinary wolf, was it? That’ll have been one of the Good People.’

‘The Good . . . Och, Nora, not your old stories about the fai—’

‘Eileen!’ Mrs Mullarkey’s voice cracked like a whip. ‘You will not be so foolish as to say the word! Not after what we’ve just seen!’

‘Whatever that animal was, Nora, it was just an animal, a

nd no more than that.’

‘Oh aye? There are more things in heaven and on earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy, Eileen O’Hara, that’s for sure!’

‘Well, even if your old stories were true, what’ – Granny paused sarcastically – ‘would they be doing wandering around here in this day and age?’

In the back seat, Bansi stirred. Somewhere in her dreams, two unpleasant yellow eyes stared unblinkingly at her through a chilly grey mist.

The sound of her grandmother’s voice came to her, as if calling her to a place of safety, and she turned. Her heavy-lidded eyes opened sleepily and she found herself in the car, gazing drowsily into the deepening twilight. Only half awake, she found herself looking at a great hill that rose above the lights of the distant village. It seemed to have a light of its own; a pale shimmer that hung around it like nothing she’d ever seen before.

‘Granny,’ she said sleepily, ‘why’s that hill glowing?’

The women looked at Bansi, and saw that she was staring blearily in the direction of Slieve Donnan – the great hill which stood to the east of the village. The hill on which the ancient stone circle lay. The hill from which, unknown to them, the wolf had come that morning.

A hill which, as far as they could see, was not glowing in the slightest.

‘Don’t you worry about that, young lady,’ Mrs Mullarkey told her firmly. ‘You just go on back to sleep. We’re nearly there now.’ She ground the car into first gear once more and moved off, uncharacteristically slowly.

Bansi’s eyelids closed again and she felt the warm blanket of sleep settle itself around her. Comfortably, she drifted off.

Mrs Mullarkey leaned over the gear lever towards her friend.

‘Maybe it’s her,’ she muttered. ‘Maybe there’s something of the Good People about your granddaughter.’

Eileen O’Hara looked as if she’d been slapped. ‘Nora! What are you saying!’

Niteracy Hour

Niteracy Hour Stinkbomb and Ketchup-Face and the Badness of Badgers

Stinkbomb and Ketchup-Face and the Badness of Badgers Stinkbomb and Ketchup_Face

Stinkbomb and Ketchup_Face Zeus on the Loose

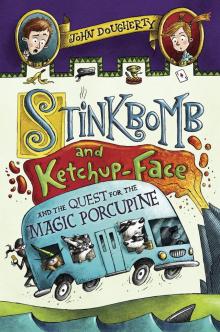

Zeus on the Loose Stinkbomb and Ketchup-Face and the Quest for the Magic Porcupine

Stinkbomb and Ketchup-Face and the Quest for the Magic Porcupine Jack Slater, Monster Investigator

Jack Slater, Monster Investigator Bansi O'Hara and the Bloodline Prophecy

Bansi O'Hara and the Bloodline Prophecy